Accessibility

IBM firmly believes that web and software experiences should be accessible for everyone. Carbon is committed to following and complying with accessibility best practices.

Carbon and accessibility

Accessible design not only helps users with disabilities; it provides better user experiences for everyone.

An accessible product should:

- Give all users the same quality of experience

- Adapt to users and situations

Carbon components follow the IBM Accessibility Checklist which is based on WCAG AA, Section 508, and European standards. The Carbon team strives to write perceivable, operable, and understandable patterns for all users—including those employing a screen reader or other assistive technology.

Individually accessible elements and components are part of building accessible products. Use this guide to design and build products that anyone can use.

Blind users

How they experience an interface

- May use a screen reader to experience interfaces

- May rely on Braille output

- Cannot be expected to use a pointer or mouse for input

What designers should think about

- Is visual information translated effectively into text? Can the image be understood through its metadata alone?

- When possible, test all designs through a screen reader.

How this applies to everyone

- As audio-only interfaces gain popularity through devices like AI assistants, users are expecting more and more from the audio representations of experiences.

Low-vision users

Low vision can include partial sight in one or both eyes and can range from mild to severe. It affects approximately 4% of the world’s population.

How they experience an interface

- May use screen readers, screen magnifiers, high-contrast modes, and/or monochrome displays

- May have their browser font size adjusted to a larger setting

- May not use adaptive technology at all

What designers should think about

- Maximize the readability and visual clarity of content.

- Consider how the relative proximity of information changes when a page is magnified.

- Follow keyboard guidelines and test with a screen reader to ensure the page is read to the user in a logical order.

- To gain a better understanding of the various low vision disabilities, use the NoCoffee Chrome plugin to preview websites.

How this applies to everyone

- Users without disabilities sometimes need to view screens in poor lighting conditions. For example, it’s difficult to see a screen outside on a bright day. A higher-contrast design will make the screen more usable for everyone.

- Vision worsens gradually starting around age 40, and good contrast helps this very large demographic use your interface.

Color-blind users

Color-blindness affects 8% of all men and 0.4% of women.

How they experience an interface

- Will not be able to differentiate between some colors on an interface

- Rely on non-color information to use an interface

What designers should think about

- Carbon color themes strive to comply with the WCAG 2.1 AA guidelines for contrast. The color palette should ensure you avoid contrast issues when used correctly. If you’re working in Sketch, we recommend the Stark plugin.

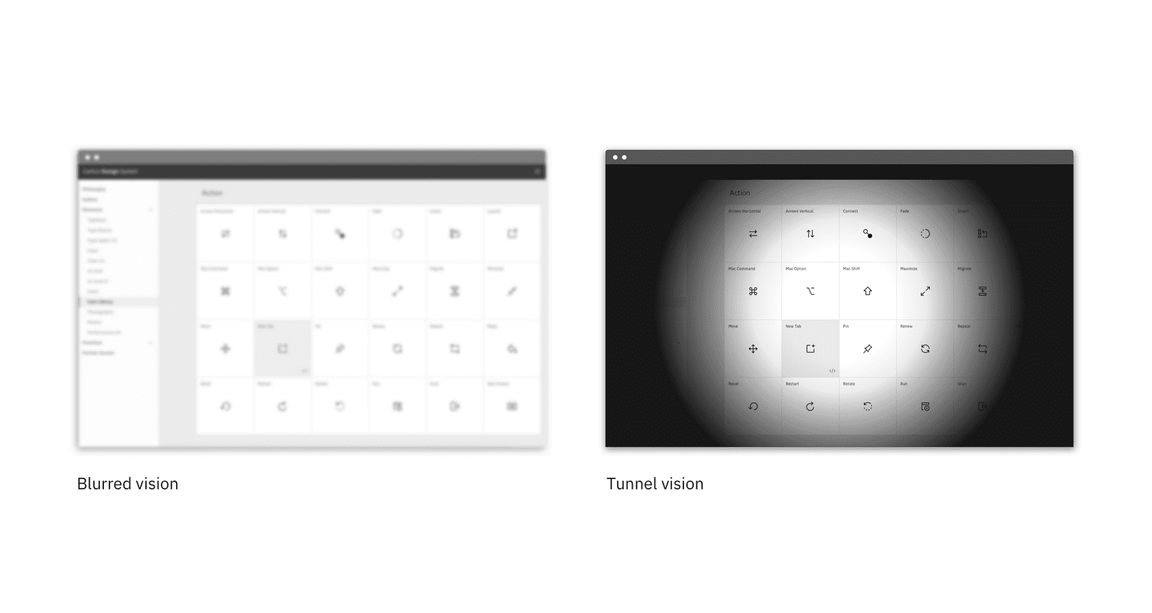

Low vision

Low vision can include partial sight in one or both eyes and can range from mild to severe. It affects about 4% of the world’s population.

| Type | Visual deficiency |

|---|---|

| Low acuity | Also known as “blurred vision”. Can make text difficult to read, since it appears fuzzy. |

| Low contrast sensitivity | Decreased ability to determine fine detail and distinguish one object from another |

| Obstructed visual field | The user’s view is partially obstructed. Can include central vision and spotty vision. |

| Retinitis Pigmentosa | Also known as “tunnel vision”. The user is only able to see central elements. |

Designing for low vision

To get an understanding of the various low vision disabilities, we recommend using the NoCoffee Chrome plugin to preview websites. Low vision users may be using a screen reader to preview your website or experience, so be sure to follow keyboard guidelines to ensure the page is read to the user in a logical order.

Deaf and hard-of-hearing users

How they experience an interface

- May rely on closed captioning and other alternative representations of audio

What designers should think about

- Find an alternative way to convey information exclusively with sound.

- Transcribe and caption all videos and animations that have meaningful audio.

How this applies to everyone

- All users can benefit from closed captioning. Imagine using your device in a loud environment or, alternatively, in a quiet environment when it wouldn’t be appropriate to turn your sound on.

Physical disabilities

How users with physical disabilities experience an interface

- May rely on keyboards, track balls, voice recognition, and other assistive technologies to interact with an interface

- May not be able to use a keyboard, mouse, or other pointer

What designers should think about

- Design for keyboard interaction

- Learn how to navigate using a keyboard and spend some time navigating the web and digital products like email using only the keyboard.

How this applies to everyone

- Many users prefer to navigate interfaces with a keyboard and no mouse for efficiency. Good keyboard navigation can help everyone be more productive.

Users with cognitive disabilities

Functional cognitive disabilities can result in difficulties with:

- Memory

- Problem solving

- Attention

- Reading, linguistic, and verbal comprehension

- Mathematics

- Visual comprehension

How they experience an interface

- May have limited working memory and need information to remain visible throughout the completion of a task

- May experience seizures when exposed to flashing content due to epilepsy

What designers should think about

- Designers should avoid complex language, autoplaying animations and videos, and flashing animations. Designs should pass usability heuristics, such as cognitive walkthroughs, to ensure users do not feel overloaded when completing tasks.

- Design in as linear a fashion as possible and focus on design heuristics that have to do with cognitive load and memory.

How this applies to everyone

- Best practices for cognitive disabilities benefit all users. Busy environments can tax your cognitive load. Aging adults may also experience a decline in cognitive abilities. Placing a low cognitive load on users reduces mistakes and improves effectiveness, regardless of their abilities.

Global accessibility standards

- World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)‘s Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) provides resources to improve the accessibility of the World Wide Web.

- Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) contributors create and maintain the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), the global accessibility standard.